By Bob Seidenberg

rseiden914@gmail.com

With little discussion Monday, Evanston City Council members voted to override Mayor Daniel Biss’s earlier veto of a local grocery tax, narrowly meeting the state’s Oct. 1 deadline for communities to make such a move to replace a recently repealed 1% state grocery tax.

Councilmember Jonathan Nieuwsma (4th Ward) made the motion to override the mayor’s veto, assuring that the city will be able to replace the expiring state grocery tax with one of its own.

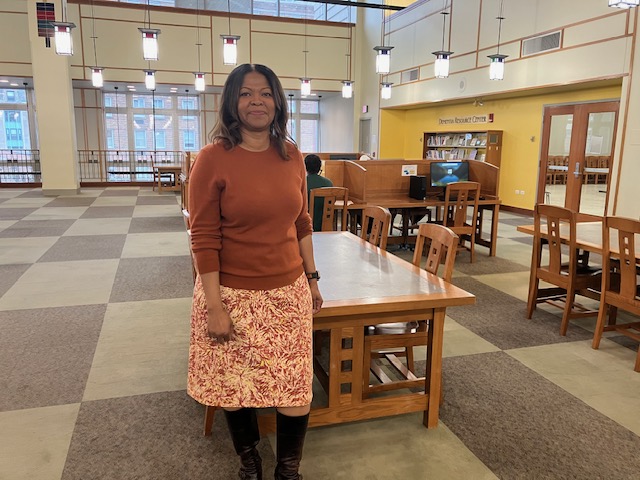

The tax generates roughly $2.5 million annually for the city with a difficult budget season approaching. The council voted 8-0 to adopt it, easily mustering the two-thirds majority, or six votes, needed to override the mayor’s veto. Councilmember Parielle Davis (7th) was not present for the vote.

Mayor: Tax would ‘deepen economic pain’

The mayor carried through on a pledge to veto the tax, announcing in a Sept. 17 message to community members that he was returning the ordinance to the council, urging them to find another solution to replacing the lost revenue.

“With food prices already at historic highs, adding an additional tax on groceries would not only deepen the economic pain for local families, it would be fundamentally unfair,” he argued.

The mayor, who is running to represent Illinois’ 9th Congressional District, also highlighted his decision a day after in an email to potential campaign contributors, noting that “my job as mayor is to make things more affordable for residents, not less.”

“People tell me everywhere I go that they’re being squeezed by higher rent, rising energy bills, childcare that eats up paychecks, and a cost-of-living crisis that seems to be getting worse by the day,” he wrote.

In a brief discussion on Monday, councilmembers held to their plans, however, to pass a local tax in place of the state one.

“This is not a new tax,” Nieuwsma pointed out. “This tax has been in place for a number of years. Less than half of this tax is borne by Evanston residents.”

Furthermore, he said, SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) recipients are not subject to the tax, he said. And “many, if not most, of our peer communities are doing this.”

To top that off, Nieuwsma said he conducted “a non-scientific poll” of residents in his own central Evanston ward, with more than two-thirds of them supporting the tax.

Councilmember Matt Rodgers (8th Ward), speaking after Nieuwsma, said he had initially expressed interest in a home rule sales tax increase to make up the revenue lost from the expiring state tax.

But with that tax facing the same Oct. 1 deadline as the grocery tax for communities to act, “that time has come and gone,” he said. “I do not think moving this to the property tax bill is the most appropriate place for it to be, and I feel that we’ve kind of been backed into this timeline and are kind of being forced to take a vote that some of us find unpalatable, but is the best solution that we have.”

Councilmember Clare Kelly (1st), said she didn’t support the tax, “but I also don’t support increasing property taxes.” She voted to go with the veto override, expressing concern that “otherwise we will be foisting more of the funds directly onto the Evanston residents.”

Grocery tax spread out

Currently, non-residents make up a majority of shoppers at Evanston stores, bearing the brunt of a grocery tax, whereas a property tax or local sales tax would fall exclusively on Evanston residents.

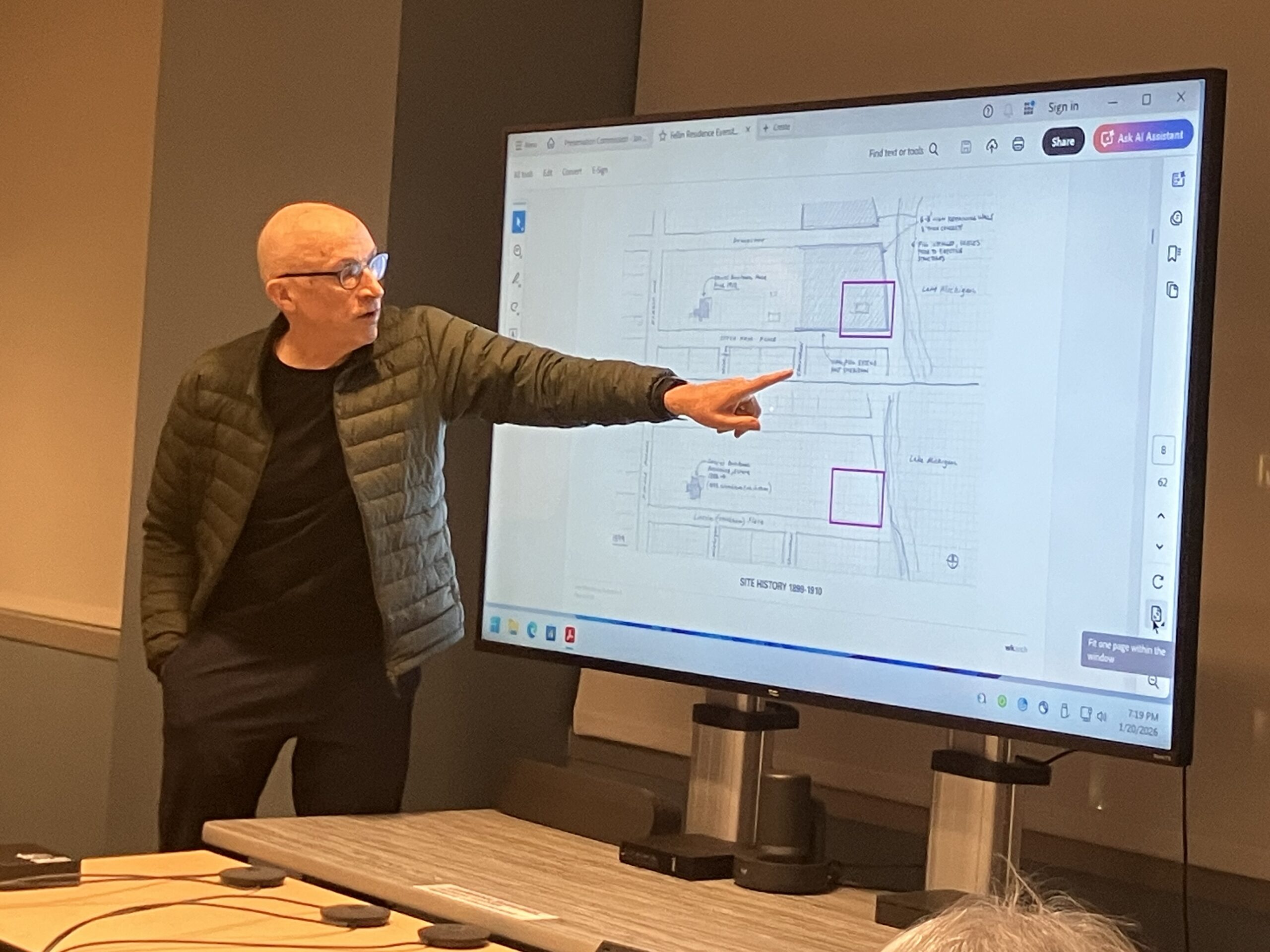

Of the eight Evanston-based grocery stores, Evanston shoppers comprise between 17% and 65% of shoppers, according to research conducted by Paul Zalmezak, the city’s economic development manager. In total, only an estimated 44% of shoppers at the Evanston stores are residents, he found.

Further, a $2.5 million increase to the property tax would result in an increase of approximately $78.53 per year in property taxes on a $400,000 home. An average Chicago household spent $6,636 on groceries in 2023, resulting in an annual grocery tax of $66.36, officials found.

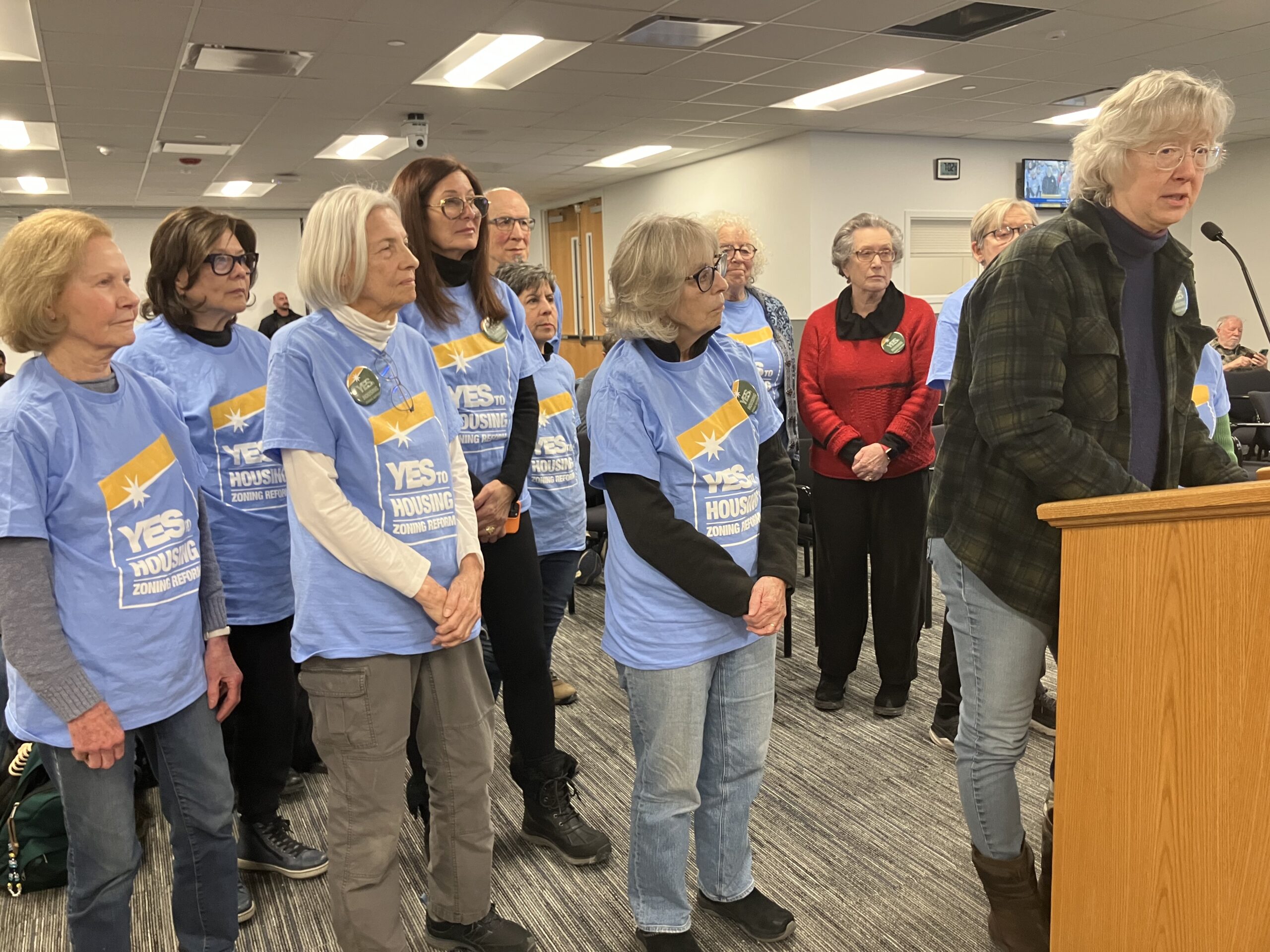

With Monday’s action, Evanston joined an ever increasing number of communities, opting to go with a local grocery tax to replace the state tax, which expires Jan. 1.

Two of the three communities on Evanston’s border, Skokie and most recently Wilmette, have adopted local grocery taxes of their own.

As of August 2025, as many as 550 municipalities statewide had opted to go with a local grocery tax as a replacement, city staff found. In Cook County alone, more than 85 municipalities had chosen that course, including Palatine, Hoffman Estates, Buffalo Grove and Schaumburg.

Chicago, though, hadn’t made a decision on whether to approve a replacement tax as of Monday. It would lose an estimated $80 million in revenue if it doesn’t meet the state’s Wednesday deadline.

A report by the Chicago City Council’s Office of Financial Analysis earlier noted that “the grocery tax is considered a regressive tax … taking a larger percentage of income from lower-income households than higher-income households. Groceries are a necessity, making the tax unavoidable even if households operate on tight budgets. … Allowing the elimination of an additional tax on necessary expenses like groceries can help alleviate strains on household spending.”