By Bob Seidenberg

Several members of the city’s Finance & Budget Committee expressed interest July 9th in exploring alternatives to replacing an expiring state grocery tax with a local one, considering other places to make up the lost revenue.

Raising property taxes, as unpopular as it may be, may be a “cleaner” more upfront way of making up the state tax’s revenue, Seventh Ward Councilmember Parielle Davis suggested during discussion.

On a grocery tax, “it’s hidden and it hits you at the cash register after you’ve bought everything.”

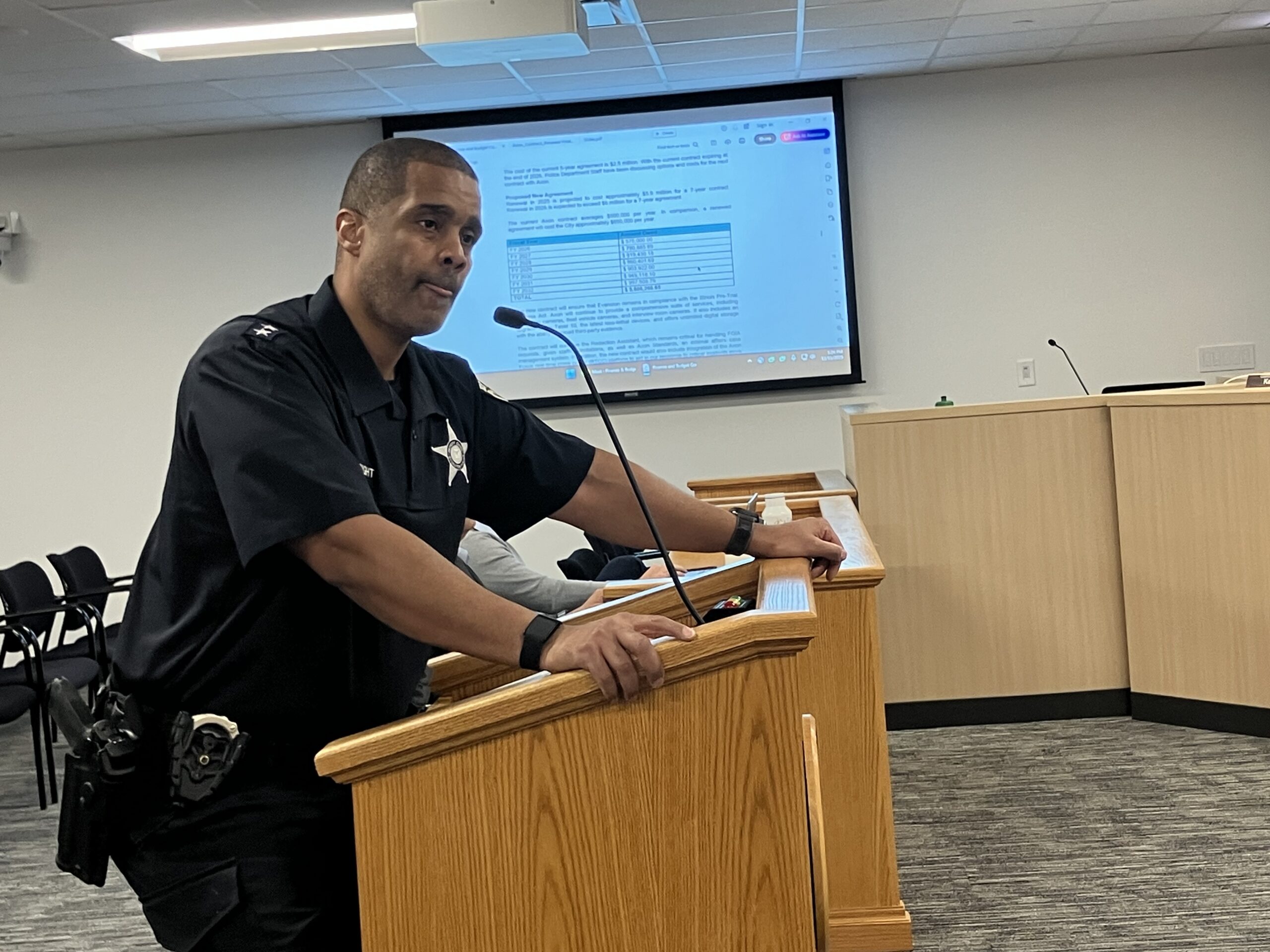

The city receives approximately $2.5 million per year from the state grocery sales tax, making it a stable source of revenue “as grocery sales do not tend to fluctuate with gains or losses in the local economy,” said Hitesh Desai, the city’s chief financial officer/treasurer, in a memo to the committee.

The state last year eliminated the tax effective Jan. 1, 2026, allowing jurisdictions to impose their own grocery tax to avoid loss of revenue.

Since then, more than 160 municipalities have adopted local grocery taxes, Desai said, including many of the city’s neighbors. Skokie is expected to pass a local grocery tax ordinance by summer’s end.

Chicago, on Evanston’s southern border, and Wilmette, to the north, meanwhile, are still in the undecided category.

The state’s deadline for cities to adopt an ordinance for a local tax is Oct. 1. If they do so after, the tax revenue will be interrupted for at least some amount of time after the new year.

Destination shoppers?

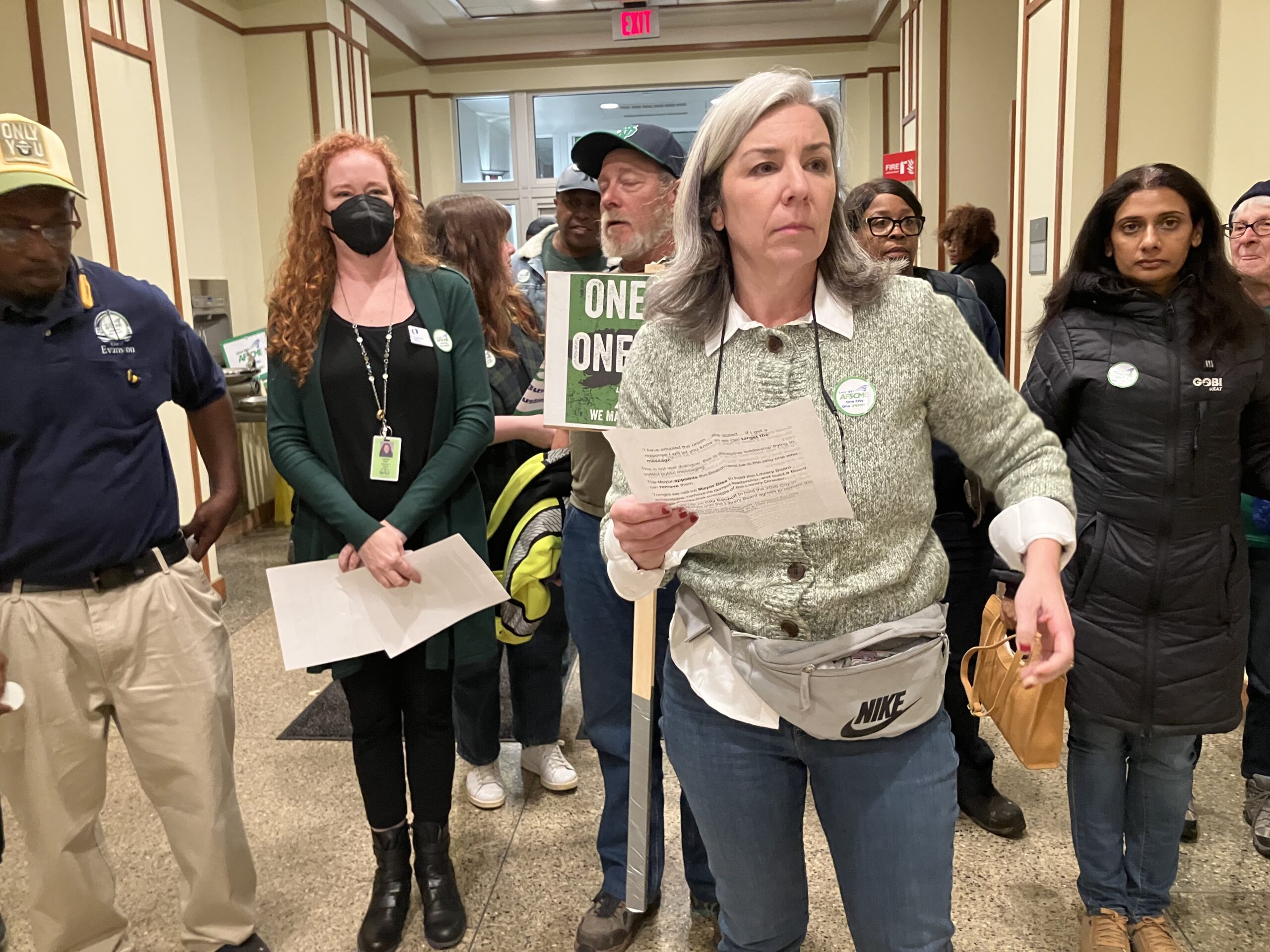

During public comment at the start of Tuesday’s meeting at City Council chambers, 909 Davis St., Dylan Sharkey, a Northwestern University graduate, and an assistant editor at the Illinois Policy Institute, a conservative think tank that advocates for reduced government spending and lower taxes, argued the $2.5 million hole the city is looking at could be looked at just as well as “a two and half million dollars in savings on food for residents,” if city officials were not to replace it with a tax of their own.

Based on the city’s population, he estimated that not moving to replace the tax would result in an annual saving of about $33 per resident or more than $130 for a family of four.

Before coming to the meeting, Sharkey said he spent roughly $30 at Aldi, making note of the paper bags he had brought along with him to the meeting.

“It’s a decent amount of food,” he told committee members. “Imagine if you could give that amount of food to every family of four in Evanston every year. I don’t think they would tell you it’s insignificant.”

He argued such a move would attract shoppers who might travel to Wisconsin to escape paying a grocery tax.

“Maybe while they’re here, they stopped to get gas, they stopped to get coffee, they stopped to get a bottle of wine or dinner,” he told committee members. “Now your other sales taxes are starting to offset that two and a half million dollars.”

In committee discussion, however, Councilmember Tom Suffredin (6th Ward) noted that nonresidents make up a large portion of those paying the grocery tax, buying items at Evanston stores.

Shoppers from outside Evanston make up about 50% of the city’s sales at local grocery stores, according to figures gathered by Paul Zalmezak, the city’s economic development manager.

The percentage of visits from nonresidents range from 35% at Valli Produce, 1910 Dempster St., to 82.9% at the Jewel-Osco at 2485 Howard St.

Turning to an alternative revenue replacement, such as an increase in property taxes, would fall strictly on Evanston citizens, Suffredin said.

“I don’t know what is gained by raising property taxes to make up for it,” he explained after.

Consulting fees a potential target: Kelly

But in further committee discussion, Councilmember Clare Kelly (1st Ward) suggested “the landscape is changing.” She referred to an article in the RoundTable, suggesting that cuts in the new federal budget and tax bill to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program could impact students at both School District 65 and Evanston Township High School.